But he did not just use the fact that he was a solo act to get laughs. He got laughs in all sorts of ways. There was a wry nod to the fact that animals used to be a popular part of the circus in the way Dimitri used a wooden horse, climbing on and off it acrobatically as he ran alongside on an adjacent treadmill. The joke was extended when the wooden horse left some fake lumps of horse shit on the stage and Dimitri had to clear it up before continuing with his acrobatic feats.

Where a classic circus would feature the clowns between the acts, Dimitri was the acts and the clowns, having fun with the wooden horse here, being hit on the head by a heavy – well, not really heavy – grain sack there. And then there was also humour within the spectacular feats too. Without his sparkly humour these acts would be nothing special. A twinkle in Dimitri’s eye holds the audience’s attention as he wobbles on the high wire. In our laughter we make an emotional investment in wanting Dimitri to succeed. The fact that he can make us laugh and then gasp as he shoots out of a cannon or bounces into the air makes it all the more breathtaking. As it says in the programme notes, Dimitri offers “a full circus programme that hovers between laughter and chills”.

At Dimitri’s show adults and children were laughing together. The circus created a bond between parent and child. The humour in a circus often has a childlike appeal, but that does not mean circus is aimed directly at children. In Tournai I also saw Ni Omnibus by Jean-Paul Lefeuvre, which blurred the boundary between adult circus and children’s circus. Lefeuvre, a lean yet incredibly strong veteran of nearly thirty years of making people laugh, used to be a part of the anarchic new circus group Archaos, who were famous for bringing motorbikes and chainsaws into the big tent and terrifying their audiences as well as making them smile.

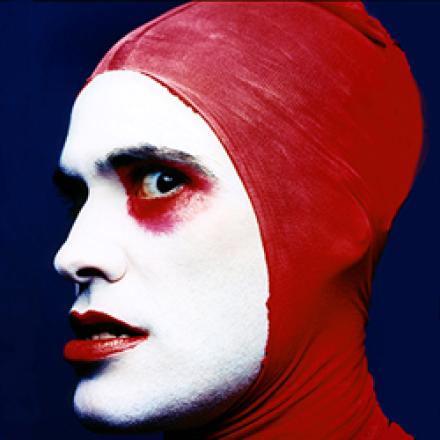

Everything was big and noisy with Archaos. Lefeuvre could not have gone further in the opposite direction if he had started his own flea circus. In Ni Omnibus the action all takes place within a set that represents the back end of a truck. The piece is wordless. It is no surprise to discover that Lefeuvre is a fan of silent movies. There is something of the hangdog expression of Buster Keaton about his face. At one point a black and white film is projected onto a small screen which, with its exaggerated gestures and jerky movements, could have been made a century ago.

A lot of the humour in Ni Omnibus comes from the restricted space. As with L’Homme Cirque, the scale of the show brings an inherent sense of fun with it. The wiry Lefeuvre bangs his head repeatedly on the roof, climbs up tiny ladders to reach things, and when he spins around on a pole he can touch the sides of the set with his feet. His sidekick, Didier André, lurks in the shadows. He occasionally wanders up to the set to throw on a broom or a torch, but behaves as if he would rather be anywhere else. This is comedy of the imagination, making something funny out of almost nothing. No special props, just a few empty wooden crates and things Lefeuvre picks up.

So far, so childlike. And in fact this show, which took place in the afternoon in a marionette museum, attracted a lot of very small children who all laughed along at Lefeuvre’s Keatonesque antics. But in a conversation afterwards Lefeuvre was keen to point out that he is not a children’s entertainer and does not make shows aimed at children. His previous show, Bricolage Erotique, was almost as adult-orientated as the title suggests. Children were allowed in but some of the ideas went over their head.

All of these shows featured highly skilled physical performers but none of them would have been as enjoyable without the moments of comedy. Circus may have evolved radically in the last four decades but the comedy element has remained important. Without humour modern circus has no chance of flourishing.

In recent years the boundary between circus clowning and the techniques of straightforward comedy shows, or even stand-up comedy, has been slowly falling away. At the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in 2012, New Zealand mime artist The Boy With Tape on his Face won a Panel Prize usually given to stand-up comedians, while the winner of the prestigious Foster’s Comedy Award was American Phil Burgers, who performs in virtual silence as Dr Brown and would quite easily have fitted into the Brussels and Tournai Festivals.